Episode 4.

- Recognize that Lifta, a place which has relationships to the identity of a people and also to a Nation, should have her cultural heritage reappraised so that she can sustain an attainable value for the evaluation of healthy civil progress for the future of this region.

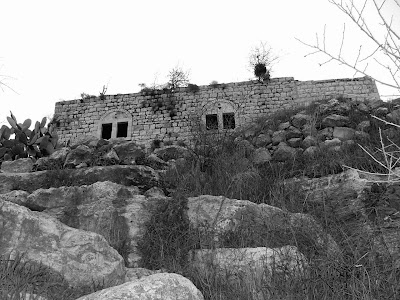

Photo: The wadi spring - the 'eye of Lifta' & 'spring of Mei Neftoah'.

Many of the structures cultivated into the landscape remain as ruins, however the spring and part of the pathway leading to it has been slightly refurbished. The spring, known as the 'eye of Lifta' still brings fresh water to its well. Once the focal point of the village, the wadi spring was used by the village ladies to wash their clothes and fill their pitchers with fresh water. Families would sit, in the long afternoons and mild evenings, telling each other of their sorrows and joys. The communal relationship that exists between the spring, the graveyard and the mosque still remains. Villagers would take the bodies of their deceased relatives to the spring where they would be washed under the trees by the spring, then taken to the mosque which was very close, and then onto the graveyard to be buried which was also in close proximity. Today, the spring is a haven for all venturing to enjoy the coolness of her water and is also encouraged by a sentiment to fulfil a purpose of ceremonial use as a Mikvah. The wadi-spring has also an historical reference as a border landmark between the tribes of Judah and Benjamin in the bible 'Joshua 15:9' and 'Joshua 18:15' as the spring of Mei Neftoah.

From the official Israeli outlook the ruins on the landscape are merely oriental remains interwoven with the mystique of the ancient past. The valley has had several incarnations and names through out her history. There are archaeological findings of a Canaanite settlement from the Bronze era. The name Lifta means corridor in Aramaic, Naftoh was its Roman name, which was then renamed Kabesta by the Crusaders. It was during the second Islamic era that it regained its Aramaic name. A few attempts have also been made to transform the valley in some form or another since the creation of Israel. Such as the use of the buildings to house immigrants from Arab countries, such as the Yemenites during the 1950s, or conserving the buildings and transforming the village into the headquarters of Israel's National Parks Protection Authority. And now the valley has been given a another incarnation under the approved plan to conserve and transform the village into a commercial edifice allocated under the guise of Mei Neptoah. The Mei Neptoah approved plan will consist of a commercial center with shops, hotels, bus stations and with land sold for individual housing on the western slopes.

Coupled by the biblical reference of Mei Neftoah the valley is attracting symbolic value amongst the Israelis. Nonetheless, even with this symbolic association one cannot override and dismiss the place is still tangible through memory and a bond that still exists with Lifta. However to have multiple values, such as recognizing ruins in association to the legacy of Lifta, is currently implausible to identifying a role with the existing context, traditions and narrative of the Israeli State. The only possibility of Lifta attaining such a value will be if she can demonstrate her necessity as invaluable and engaging at a level akin to a progression and goodwill for the region. Therefore, any value has to be able to penetrate the imagination of the Israeli consciousness and National narrative. However, in her current form, Lifta only sustains a relative value as a place with an identity through memories held together by a bond. By acknowledging that the principle agent and influence sustaining the place is the bond, it will be necessary to demonstrate if this bond can also redefine its location within a definable context of the Nation State.

The potential to demonstrate the accessibility of this bond is possible through further examination of the location. Currently, the ruins on the landscape lies disparately as if frozen in time between two epochs, two histories, and the two dominant cultures of the region; a place in-between and connecting two paradigms. The event that occured during the uprooting of the Palestinian and the establishment of the Israeli is inextricably tied together by a context which needs reason behind one historical event to explain the other. Traces of the event are preserved and made tangible only through the memory sustained by a bond to the ruins. Lifta reveals a dissonance and conflict that arose in the uprooting of this village is inextricably tied together to the creation of the Modern State. She is a contextual origin whereby the struggle of the Palestinian people that has perpetuated from the events of 1948 and the genealogy of Israel's history can be traced back to her location as a point of departure. The current issues of dissonance between Israel and the Palestinians seen unfolding in the present context have their origins traced to a place whereby the source of the conflict becomes tangible.

This conflict that defines this particular moment in history has essentially unfolded into the current existential values of today. Part of the influence of their constructions are achieved through a protagonist quality of dissonance, a staging of a conflict of values, constructing differences and establishing the 'other'. If the State allowed the removal of the signs of history, that is still tangible, it would be detrimental in erasing an historical location that forms part of their current existential truth. A place that reveals the creation of the two dominant existential identities of the region; a 'point of departure' of the two current narratives of the Israeli and the Palestinian. Lifta is a unique insight into truths that are crucial to understanding part of the nature and construction defining identities. The two existential narratives opposed in conflict share the same story through the same language of a reality through the given context of Lifta. What the narratives oppose of one another is also brought together by this place. The language of history of the Palestinian and the Israeli are bound and concealed by a place. To fail to recognize Lifta is to also to deny both Palestinian and Israeli history.

The importance of the relationship of the bond connecting memory and place here is that the common history is sustained through an origin. It is a common history that is tangible and a particular history that needs to be re-visited as well as engaged by both parties inextricably tied together to the conflict. Lifta as an apparatus can allow us to contemplate and attend to issues involving dissonance and history by stabilizing memory through a duality. Memory is an invaluable resource and a principle reason for officially wanting to have this place recognized. Memory can provide a stage of communication for those confronting the undeniable raw emotion of trauma and a denied sense of anguish and loss. Memory thus re-inventing a place that has the opportunity to deal and tangibly confront the tragedy. It is through such a common-ground that a gathering involving both sides represented in the conflict can in some instance be imagined. Creating the capacity of a space for the sake of openly redeeming rather than reservedly confining the existential natures of identities. The bond provides the capacity to engage with a space envisaged to create acknowledgement for the purposes of reconciliation.

The consequences of the situation today can be understood by a place that locates its entirety into a context. An historical point of origin that has the capacity to engage at the tangible constructions of the making of confrontation, differences and narratives. Locating Lifta in this particular historical context, confronting the real experiences of the conflict of 1948, is important for acknowledging the tragic events of history. Insubordinate and vulnerable with current reality it may shamelessly be however, the necessity to give insight into this place is not conceivable unless it seeks to create an opportunity from the definable differences. As a common-ground Lifta verges onto a space of encounter, but can she continue to voyage further into a space of the possible? For instance, can reciprocation of the bond between memory and the ruins have the capacity to sustain an all-encompassing sense of justice and truth towards the lost temporal landscape? Or in the pursuit to illuminate genealogy, can the common past be used to resort to reconcilable narratives and situations? So by contesting history can a challenge be set against the moving spirit of dissonance notably characterized within the current situation of the region?

Lifta's last moment during the upheaval of her cultivated platform lay besieged to a conflict. Thus creating an origin that perpetuated into the region's struggle between the two existential narratives of the Israeli and the Palestinian. Either of the cultural narrative's intent and actions can have the effect of creating a counteraction synonymous to a dissonance producing 'otherness'. For instance, attitudes and outlooks of a cultural narrative can interpret situations or a version of events performed by the 'other' as inconsistent and contradictory. The eventual action of response between the narratives can have an effect of reproducing values of difference and discord thus sustaining a potential conflict. The question remains can a likely removal of this central character of dissonance be accomplished if the desolate valley that is an origin of the conflict and two narratives was to stage a meeting with the 'other'? Can using a common-ground enable the possibility of a reality to be accessible to both narratives with the same mutual acknowledgement? And can the common-ground be capable of contesting the events of a particular poignant moment in history whilst encouraging a dialogue towards an all-embracing judgment?

The central character of dissonance can be interrupted if the prominence of the conflict of narratives is reduced by converging on truths that readdress traditional conceptions. The idea and impression of Lifta as a contextual genealogical power origin to the Modern State of Israel is an argument tended towards addressing the creation of dissonance. The interaction of people with a memorial preserving a specific historical period plays with the idea of relevant cultural objects that evoke a new interplay between histories, cultures and place. A need for this particular intervention serving as a place of observation creates an opportunity to question and examine cultural assertions. Demonstrating to educate people about the past for the urgency of reconciling discordant situations in the present context of civil society. Nonetheless, reinforcing history can prove to be an obstacle especially if it required officially acknowledging Palestinian memory about the origins of the conflict. The challenge is finding approaches that can make communicating to broader audiences compatible and acceptable. And the memory of Lifta has evidently more to impart with to allow such a capable intervention.

Language can make realities accessible. Language processes experiences through recognition and interpretation, therefore allowing us to ascertain realities. Israel has a traceable genealogical power origin that recognizes an identifiable character within the current identity of the State. A place where language can recognize contextually and interpret the legacy of the divide of the two main existential narratives is tangibly accessible and can be absorbed, but nonetheless is not immune from being interrupted. This point is significant as the same language has the capability of making other realities accessible and therefore accessible to a same narrative. The bond to the ruins bears testimony to a quintessential form of civil behaviour, allowing a memory of civil equality to be evoked whilst sustaining a unique insight into the origin of a lineage of historical conflict. Both the genealogy and ontology directly connected to this place offer an ideal and significant opportunity towards providing an historical foundation for reconciling conflict. Memory can be utilized for ascertaining realities to introduce the possibility of new constructions; consequently, the possible ramifications might enable a power origin to be subverted through the common-ground.

Genealogies are important because they can also be identified and distinguished as power systems. Power as control or force can commonly be interpreted within historical social conditions as motivations and attitudes. Genealogies as power systems contain and carry belief systems that define the very nature of our behaviour or nature of being; ontology. Genealogical origins sustained within histories, memories and tangible traces have the capacity to nurture and cultivate future successions of behaviour. (for example, the relationship between the creation of a genealogical origin of the Modern State of Israel and the creation of dissonance.) Nonetheless, rather than resuming specific modes of reproductions as a linear series of ongoing motivations, genealogies can also have the capacity to restore alternative modes of behaviour previously retracted and deemed unnecessary; evolving the ongoing ontology of a lineage. The idea of Lifta as a contextual genealogical origin to the Modern State of Israel is that the argument can be used to create an observation of place that can prove important to the current context and social values. Civil equality as an ontological value can serve to break down obstacles whilst contributing on it's own qualities to readdress a social heritage.

Upon reflection, the uprooting of the village was a tragedy for the palestinian community of the village however, the community encompassed multi-ethnic groups. The Nakba in Lifta was a catastrophe for the palestinian muslims, christians and jews. The jewish Hilo tribe, who apparently were given the option by the pervading force to remain in the village, decided to share the same fate with their community and vacated the village. There is historical evidence that gives reason to believe that this event encompassed a discord for all ethnic groups associated to it. These insights fully deserve to be accounted, recognized, as well as expressed; they provide significant opportunities for suggesting outlooks that provide alternative views upon the region's history and place. What is interesting is that new insights can begin to create a working of a new narrative, a new history, and a new space. The creating of this space which recognizes experiences of both the conflict and of civil equality begins to contests its' own history. The fact that the same language, through and because of a memory, sustaining a history of civil equality 'meets' with the reconstructive language of the conflict means that the acknowledgement of this connection of histories can possibly have influence on a new consciousness making. Where one is aware of their environment and of a space for the re-imagined.

There has to be some form of social upheaval that is constantly reminding the environment of truths such as civil equality, so to bring some form of contradiction and ambiguity of power contesting the ideology of the environment. Again, through investigative examination into Lifta's memory and juxtaposing truths such as that this place unfolds a story of a tragedy, or is relatively a contextual origin for Israel, and where a multi-ethnic community once thrived - may allow further contestable narratives to be obtainable. Memory can influence the necessary negotiation needed to sustain a dialogue on the recognition of truths underlining currents of genealogical and existential constructions. Again this is significant as it can allow the potential capacity to address issues that fundamentally seek reconcilable possibilities. Exploration of memory can become paramount in creating and enabling mechanisms to defuse the attitudes that translate into a language of adversity and dissonance of the differing existential beliefs. Conducting further research into Lifta's memory and juxtaposing truths can possibly allow further contestable narratives and introduce new possibilities for the reconstruction of heritage. So rather than asking who officially gets the right to choose or imply history and heritage, a need to preserve and develop instruments that actively seek to contest truths can be envisaged as a devisable method for this common-ground.

So what is the objective? Is the objective to sustain the preservation of Lifta so that she can be clearly recognized as a place, or is the objective also to introduce a monument into the environment whom's equivocal workings is aimed at addressing the conflict? Both. The valley landscape should be noted for her many encarnations, from the early Canaanite settlement from the Bronze era, and including the present practices such as the attraction of her natural spring that fulfills the ritual as a mikvah. Nonetheless, there is also a credible history that is invaluable to the present situation and context of identities in the region. A heritage that can allow an acceptance of truths that can bring together both sides of the conflict to share the same grief and hope and reevaluate relationships for the sake of the regional community. Symbolism of place can confirm power and control over the environment; identities can be inclusive and foundational just as they can be exclusive and oppressive. Saving Lifta is only likely to be achievable if she asserts values that are inclusive in her objective of becoming recognized as a place. And a desire towards a monument that can convey new meaning and understanding as well as offer alternative capacity building can prove invaluable. In prospect, an attainable value through the reconstruction of heritage; aiming to bridge worlds together by creating mechanisms out of a bond between memory and place.

Next time.....the tools devised for action will be highlighted, thus unfolding the manifesto and taking the next step into the journey of the grassroots activism.

written by Anil Korotane, Architectural Activist, FAST.